Going Global Powers Growth in Post IPO Companies

Written byMorgan Livermore

If you’ve read TechCrunch, the Wall Street Journal, or any blog post for the last few years, you’re surely aware of the rise of the unicorns, the speculation of a tech bubble, and the massive funding rounds for private companies at seemingly indefensible valuations. How we got here should come as no surprise. Investors chase alpha. So when headlines read of big exits, investors come stampeding (see here). More funds and investors mean more dollars chase the same investments. Competition drives valuation inflation. Additionally, thanks to the economic stimulus, buyers (PE and companies) have access to cheap capital through low interest rates, some of which they use to make big purchases, creating that coveted alpha for investors. Rinse and repeat until the music stops. But the music hasn’t stopped; the beat goes on. But investors (generally) aren’t irrational, so how can they justify continuing to invest as they have? Could there be more to the rising valuation narrative than just cheap capital and exuberant investors? We looked at tech IPOs since 2010 and the story (or at least part of it) is more nuanced. Companies have grown larger, scaled faster, and become more international before going public than ever before.

Some Not So Quick Data Analysis For Context

The additional capital companies raise in the private markets helps them build more solid underlying companies so that when they go public, they are bigger, growing faster, and have more defensible technology. We pulled publicly available data on every U.S. tech company that has gone public since 2010, removed companies that had previously been taken private or were spinouts from other businesses. We were surprised and encouraged by what the data told us.

Companies are staying private longer, but not as long as headlines might indicate. The dataset tells us the average time to IPO has increased only slightly, to 11.4 years in the last 5 years, compared to 10.7 years from 2010–2014 (see chart below).

The rise of “private IPOs”, or large private capital infusions before an IPO, certainly delayed IPOs a bit, but not as significantly as we thought. Companies are effectively the same age when they go public as they were a decade ago.

The biggest difference between companies going public from 2010 to 2014 and 2015–2019 (the timeframe where the rise of unicorns and private IPOs has been more heavily scrutinized) is the scale and growth profiles of the companies. For the dataset, the average LTM revenue at IPO for companies that IPO’d from 2010 to 2014 was $164m compared to $291m* for companies that IPO’d in the 2015–2019 timeframe.

With LTM revenue 150% higher in 2019 than in 2010 and 77% higher using 5-year averages, the data tells us that company building happens at a faster pace than ever before. Instead of gawking at unicorn valuations, we should applaud today’s entrepreneurs for building bigger, faster. There are many ways to create value, but ultimately, investors — private and public — ascribe value to companies that are differentiated and scaled while still growing rapidly and that’s what today’s entrepreneurs are doing.

Scale, Growth, and Expectations

The law of large numbers makes growing at scale difficult and the additional time and capital raised both come with bigger expectations. Startups must be able to demonstrate to investors that they will grow for many years ahead. So how are these companies able to grow faster and larger in a shorter period of time?

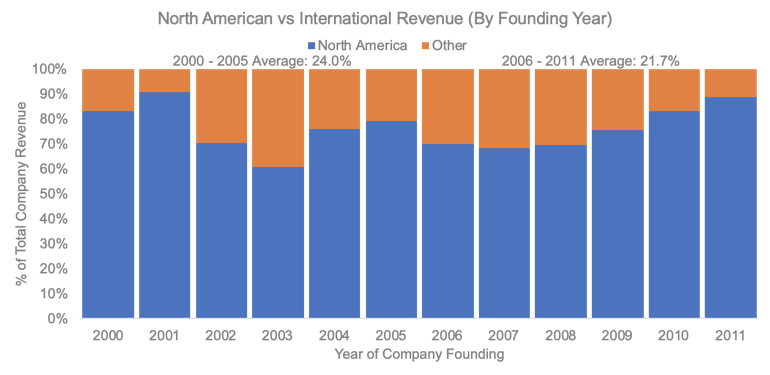

One way companies achieve growth at scale is by looking overseas. Across all of the companies we analyzed, we noticed a significant piece of their revenue was from non-North American sources, about 30% in fact, across all companies that IPO’d since 2010. As expected, a company that was founded 10 years ago tends to have more international revenue than one founded 2 years ago as companies that have been around longer have had more time to build a presence internationally.

But we know companies that have gone public in the last five years are bigger when they do, despite only being a year older on average. So we looked at the international makeup of companies based on when they went public and the results were pretty consistent: both cohorts average ~29% (29.4% for 2010–2014 and 29.7% for 2015–2019) international revenue, irrespective of when the company was founded.

With consistency, U.S. companies going public have 29% of their revenue generated in overseas markets.

International Expansion

Every company is different and international expansion should be carefully considered for each company’s own circumstances, but proper execution can lead to massive opportunities and significant global advantages to those who do it right. For newly public (particularly high-burn) companies with high valuation expectations, growth must come from places other than improved execution and product innovation — overseas markets are a logical place to look.